Glenn McCartney

PhD, MBE. Associate Professor in Integrated Resort and Tourism Management, University of Macau

The need for a clear definition of what diversification is, including its potential impact to the Macau economy, has become increasingly pressing due to the significant economic losses incurred by the pandemic and the subsequent travel and health mandates enacted in the city and mainland China. Diversification is a remedy to the ‘dutch disease’ phenomena (an economic term to describe when one industry becomes so powerful that others are pushed out of the market) which onset in Macau many years back. A downside to ‘dutch disease’. Is that while the balance sheet looks great, things can unravel should that solitary industry be impacted. In this brief summary, I present key considerations to Macau’s diversification.

The need to remedy the economic losses to Macau’s casino industry presents a challenge to a diversification pathway being implemented even in the short term. There are considerable daily revenue loses and debt accumulation by the six gaming concessions – their natural drive to create efficiencies and cost cutting measures has had a rippled effect to several other industries who directly or indirectly benefit on casino growth and success, such as retail estate and restaurant sectors, including multiple SMEs and suppliers. Increased unemployment – principally to non-resident workers – leave HR departments juggling on cost reduction measures while trying to keep the hospitality workforce motivated. Other externalities such as the decline of VIP has added to the woes of the industry including travel restrictions and targeted lockdowns remaining possible due to the zero-tolerance position towards COVID-19 in mainland China and Macau.

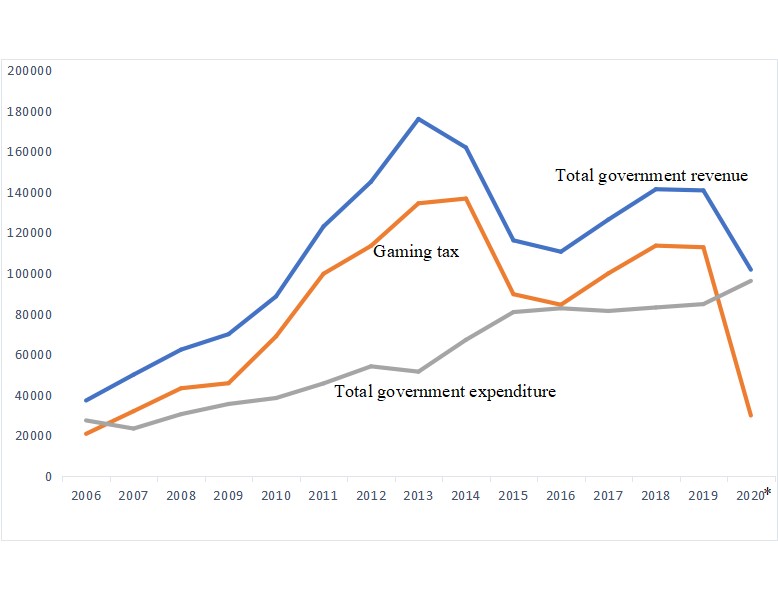

Diversification must create alternative sources of revenue, taxation and employment. So, what does it mean in the context of Macau? There are 5 key issues – first, it revolves around the gaming to non-gaming revenue mix as an indicator of diversification. In 2019, casino tax was 80.1% (USD14.1 billion) of total taxation contribution to the government of USD17.6 billion. Macau’s public purse has become increasingly reliant on this single tax source, with annual surpluses until 2020 adding to Macau’s fiscal reserves. In 2006, Macau public finances received 56% (USD2.6 billion) of its total tax (USD4.6 billion) from the gaming sector. There was clear indication of ‘dutch disease’ occurring – this fiscal trend confirmed limited economic diversification was setting in. According to the World Travel & Tourism Council (WTTC), total contribution of travel and tourism to Macau’s GDP in 2019 was 83.9%. This dropped by 79.3% in 2020 to 43.4% of Macau’s total economy.

Macau’s total tax and revenue in millions MOP (source Macau Statistics & Census Department)

Secondly, diversification should present a clear demarcation of non-gaming sectors involved – this can be accommodation, retail, restaurants and bars, leisure (spa, recreation), technology, event and entertainment, MICE (meetings, incentive travel, conventions, exhibitions), finance, medical and so on. Through this, and to my third point, policies and incentives to assist in their development can be applied. A major policy being discussed now is the Gaming Bill – the outcome will be a public tendering and criteria to award casino licenses, and a window of opportunity to present diversification KPIs. A collaboration of policies (eg. tourism, labour, casino) between the public and private sectors could advance this.

Fourth, it is clear that diversification must come within the tourism sector, supported mostly by mainland China travelers which now makes up over 90% of visitation to Macau. A report from the WTTC in 2018 placed Macau as the world’s most reliant city on tourism. Over half of Macau’s economy was supported by travel and tourism (for Las Vegas it was around a quarter).

Top 10 largest cities

(Direct travel & tourism contribution to city GDP, 2018, %). (source WTTC, 2018)

| 1 | Macau | 50.3% |

| 2 | Cancun | 46.8% |

| 3 | Marrakech | 30.6% |

| 4 | Las Vegas | 27.4% |

| 5 | Orlando | 19.8% |

| 6 | Dubrovnik | 17.8% |

| 7 | Dubai | 11.5% |

| 8 | Bangkok | 10.6% |

| 9 | Antalya | 10.1% |

| 10 | Miami | 9.2% |

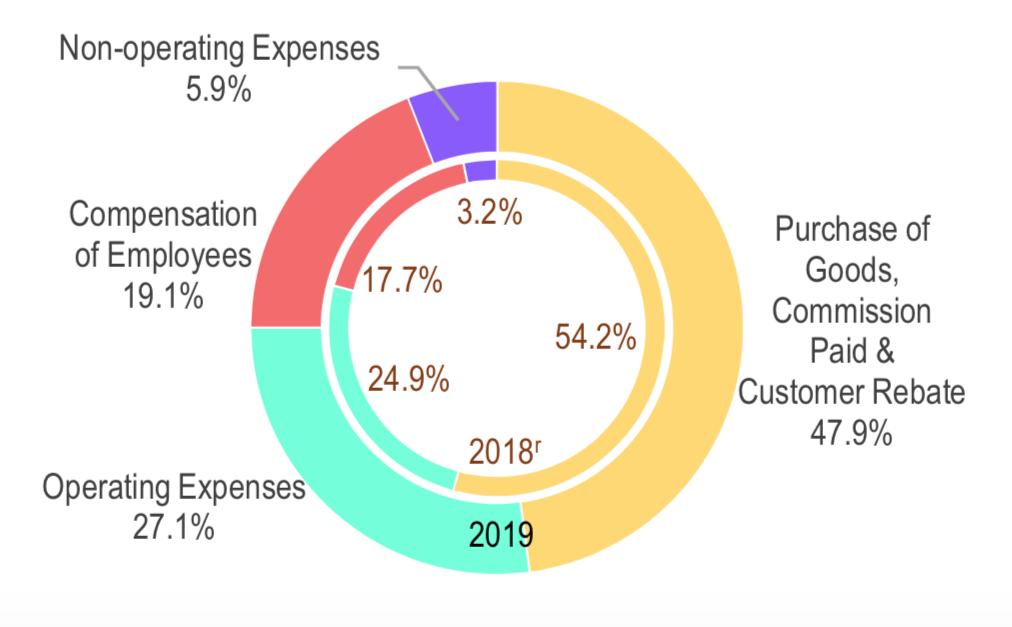

Some of Macau’s non-gaming is already intertwined with the gaming industry. The casinos had an operating cost of USD14.7 billion in 2019, 27.1% (USD4.0 billion) of which were operating expenses – 52.9% of which was complimentary (or ‘comps’) goods and services to customers. The biggest benefactors of the ‘comp’ system have been accommodation and food and beverage. Diversification would mean attracting wider visitor markets to Macau to spend more in these non-gaming markets.

Gaming Sector Survey 2019 – Structure of Total Expenditure (Macau Statistics & Census Department)

There are casino tourism diversification case studies. Las Vegas made the gaming to non-gaming dominating switch in 1999, with non-gaming representing 65% of the Las Vegas Strip revenues in 2019. There are certainly criteria by which to chart a sustainable pathway to Macau’s tourism diversification future.

Further insights into Macau’s diversification and future development are presented in greater detail in ‘Macau fortunes: Customer evolution accelerates post-COVID’ CLSA U Bluebook authored by Glenn McCartney and Jonathan Galligan (Deputy Head of Research at CLSA, HK)

- World Travel & Tourism (2022). Global Economic Impact Reports. https://wttc.org/Research/Economic-Impact

- Macau Statistics & Census Department (2022). Macau in Figures. https://www.dsec.gov.mo/en-US/Home/Publication/MacauInFigures

- World Travel & Tourism Council (2018). Key Highlights – Economic Impact of Cities 2019.

- Macau Statistics & Census Department (2022). Gaming Sector. https://www.dsec.gov.mo/en-US/Statistic?id=406