Preserving a dying language is something that takes community effort and passion for the culture – something local drama group Doci Papiaçam di Macau has been attempting since 1993.

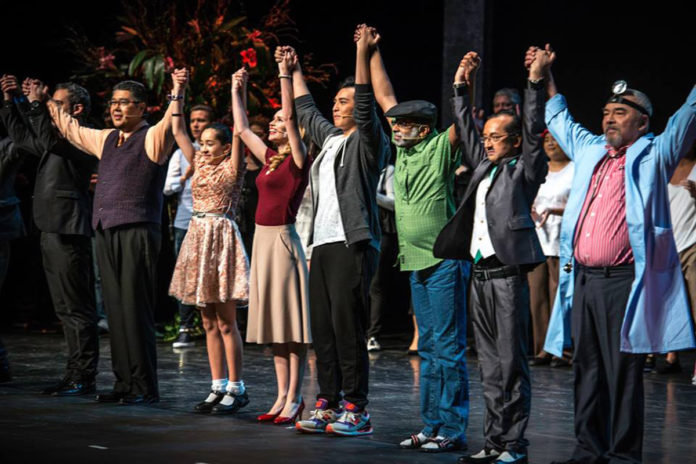

As usual, the group will perform a play enacted by local actors and entirely in Patuá – also known as Maquista, Patois or Macanese creole – as part of the 28th Macao Arts Festival, with this year’s play ‘Sórti Na Téra Di Tufám’ (Stormy Luck) staged on May 19 and 20 at 8:00pm.

Performed only in Patuá – with subtitles in Chinese, English and Portuguese – by local amateur actors, the story revolves around local resident Bernardo who is haunted by bad luck but one day discovers he has won the Hong Kong lottery.

However, an incoming typhoon threatens to hit the two cities and block him from claiming his prize, with the lucky ticket becoming coveted by the other characters in the play.

“This group is an attempt to keep the language alive as Macanese tradition. We’re all amateur actors with other professions and we don’t speak it every day. Some of our actors had only heard Patuá but had never actually spoken it,” one of the plays actresses, Sonia Palmer, told Business Daily.

Ms. Palmer has acted in almost all of the 24 plays performed by the group and considers herself a Patuá speaker able to understand “at least 90 per cent of the language”.

Despite their daily jobs the dozen or so actors that usually take part in the plays managed to find the time from their jobs for three months to prepare a show they see as a way to “remind people the language exists”.

Their effort is generally rewarded with full houses in their two annual shows, attracting people from diverse nationalities interested in the language or in the group.

Language of satire

The existence of the group has much to thank lawyer Miguel Senna Fernandes for who has been the playwright for all of the 24 plays performed thus far.

The son of renowned Macanese writer Henrique de Senna Fernandes, the lawyer has also managed to find time to hold down the post of President of the Macanese Association (ADM) and nurture his passion for Macanese culture and history.

“It is a passion I am dedicated to with body and soul; when you really love something you find the time,” he told Business Daily.

According to Mr. Fernandes, reviving the language involved an effort of “upgrading” and including modern expressions that did not exist in the traditional vernacular.

“I had to imagine what a Patuá speaker in the contemporary world would say when faced with computers and the Internet. How would he say download or upload? Every language evolves, and the whole definition of creole is about being pragmatic and adaptable,” said Mr. Fernandes.

As usual in the group’s plays, aside from the humorous aspect it includes a great amount of social and political critique on Macau society as part of the long tradition of Patuá being used for satirical theatre in the city.

“Even if the language has lost its daily use it remains a language for criticising or satirising the powers that be. It’s the language of the mistreated and it’s part of that tradition to use popular expressions and dialects in satirical theatre,” the playwrite told Business Daily.

Fernandes says the inspiration for this year’s story theme was the controversy surrounding a typhoon alert last year when the city’s authorities raised a Signal 3 for Typhoon Nida despite the neighbouring regions having raised a Signal 8 alarm.

“That event inspired the story a lot – but the humour of the story doesn’t come from criticising someone or any department in particular but by the whole inevitable typhoon situation,” he says.

Luck is also one of the main themes of the play – an issue “very prevalent in Macau” – with the main character being in possession of a HK$90 million lottery ticket while being unable to cash it in.

“With the ticket becoming the coveted target for other characters we delve with humour into the theme of people’s integrity and honesty,” Mr. Fernandes told Business Daily.

A spoken travel route

Patuá is generally described as a creole language, evolving from a combination of the Portuguese language with dialects from the country’s former colonies in Asia and Africa, such as Malay from Malacca and Sinhalese from Sri Lanka.

It has been spoken by the city’s Macanese community as Portuguese explorers settled in Macau in the 16th Century, which at the time was the first Western commercial outpost in China authorised by the Chinese Emperor.

“Languages don’t appear out of nowhere. The language is part of Portuguese roots brought to China during the golden age of the country’s explorations. When analysing the linguistic elements of Patuá we see that it tells the history of Portuguese discoveries, possessing elements from Africa, India, Malacca and later Cantonese. It’s a spoken travel route,” said Mr. Fernandes.

The Patuá researcher believes the language is a branch of a common language used by Portuguese in their contacts with different ethnicities and people in the region that evolved into a real language with grammatical and syntax rules.

“The language is described as a mash-up but every language is a mash-up. It’s a cocktail of languages that passed the blender but managed to evolve and form what is Patuá,” he added.

The language is considered by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) Atlas of World Languages in Danger as being ‘critically endangered’ with the organisation having set the number of speakers at just 50 in 2000.

Mr. Fernandes, however, believes the number of Patuá speakers at the moment could number around 500, with the number of speakers of the traditional and “more dense” Patuá much smaller.

In 2012, Patuá theatre was considered by UNESCO as an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Macau with the lawyer saying he is preparing an application to glean Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity status.

“Patuá is a language phenomenon that can’t be placed in the corner,” Mr. Fernandes concluded.